The Concept of Two Powers in Heaven

I recently watched a video from Rabbi Tovia Singer. The caller shared a story about Christians distributing books claiming that Jews historically believed in “two powers.”

The doctrine of “Two Powers” is the belief that there was a person distinct from God, yet equal to God at the same time.

The caller posed an important question about whether early Jewish tradition involved worshiping two powers in heaven.

The question arises from claims that early Jewish traditions hinted at a belief in multiple divine figures [Father and Son]. This idea has fuelled debates between Christian and Jewish scholars, particularly over passages in the Hebrew Bible.

But what does historical evidence and Rabbinic tradition reveal? Let’s find out.

Before we continue, I want to make it clear that my use of Rabbinic tradition, and historical evidence, is to showcase that Rabbi Singer is not being true to the tradition he says he believes in.

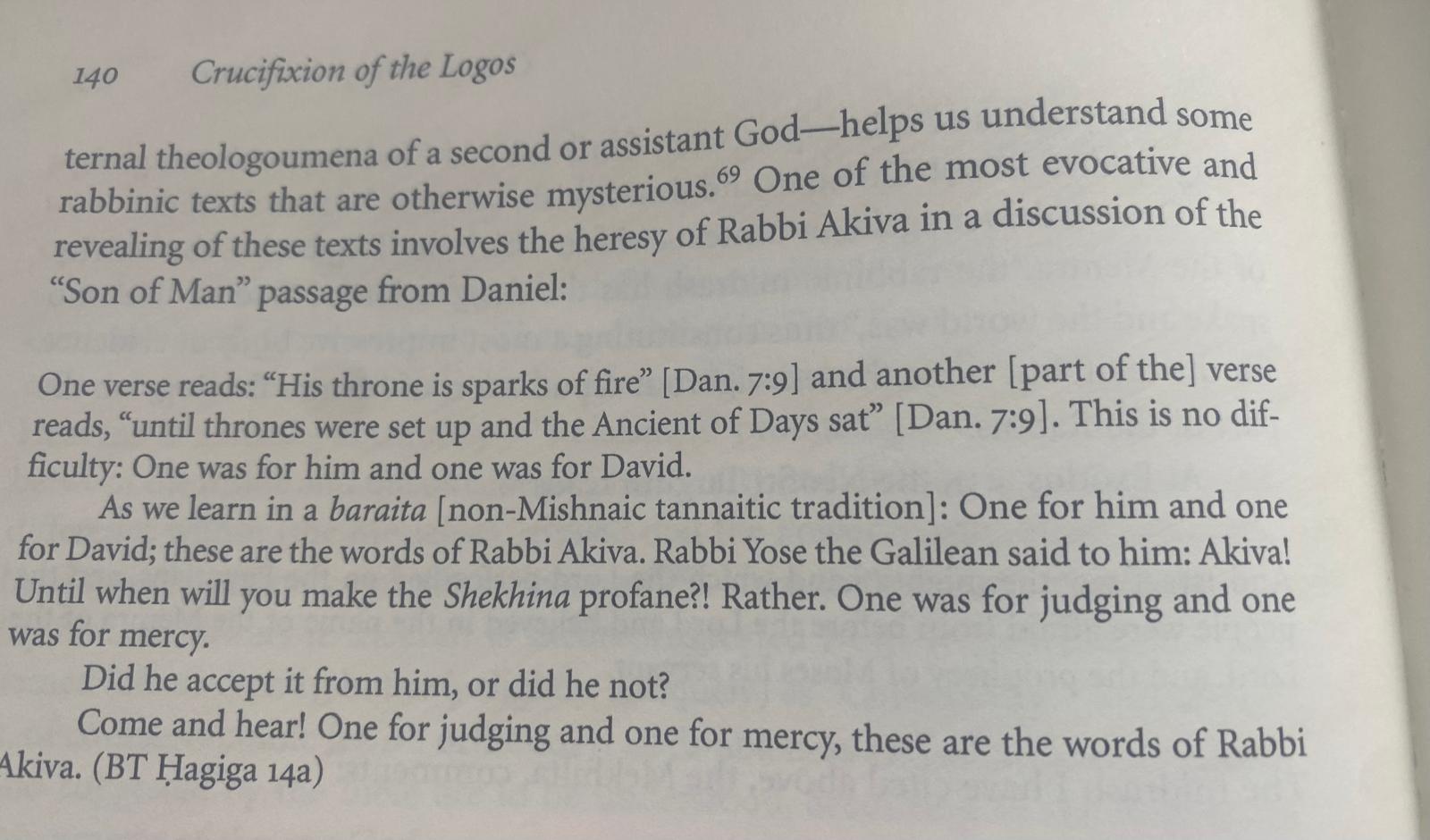

Rabbi Akiva and the Son of Man

A pivotal figure in this debate is Rabbi Akiva, the most revered sage in Rabbinic Judaism.

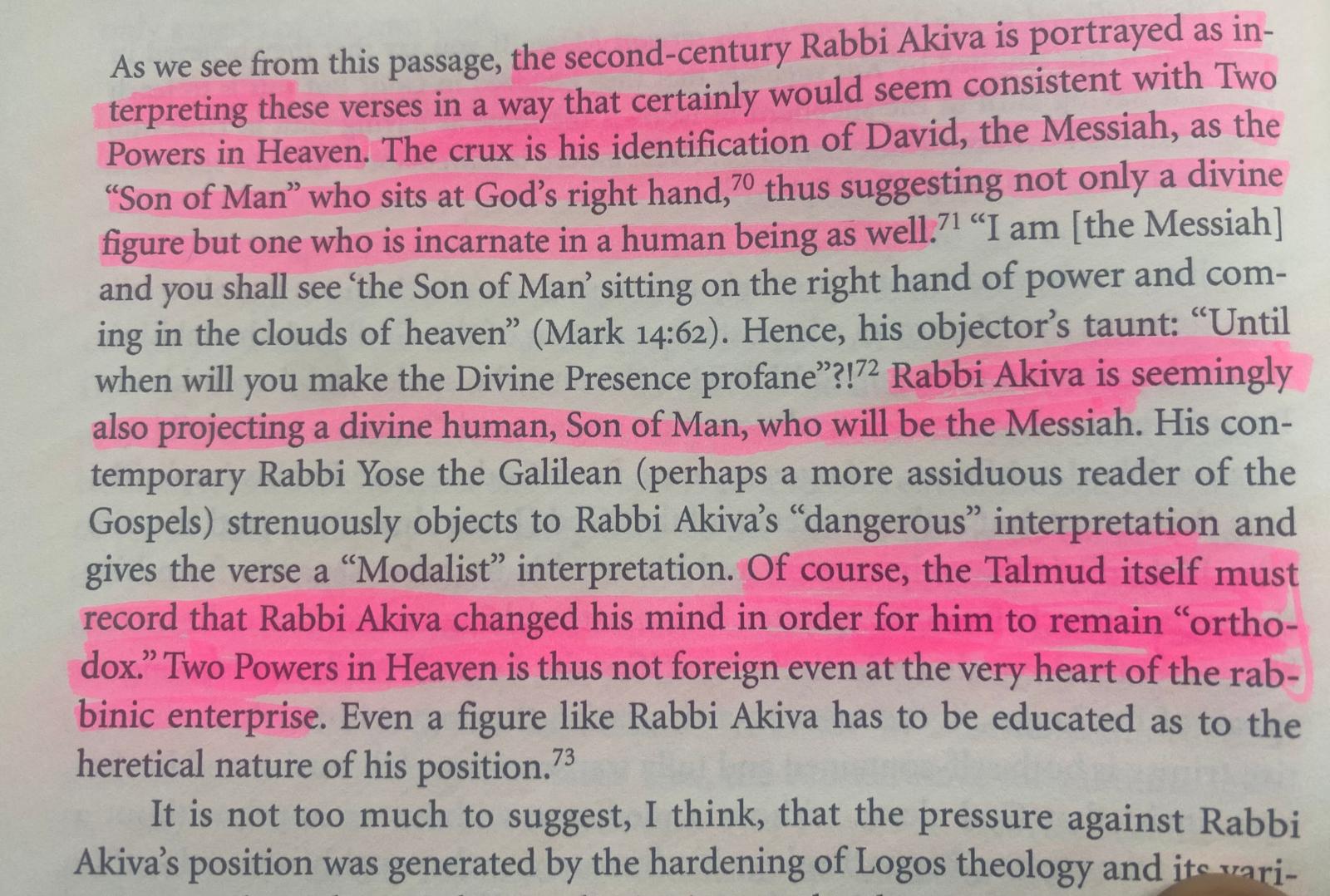

According to Dr. Daniel Boyarin in his influential book “Borderlines“, Rabbi Akiva’s interpretations of certain Biblical texts reveal a complex understanding of divinity, that suggests a duality within the heavenly realm.

Specifically, Akiva’s interpretation of the “Son of Man” in Daniel 7 highlights the notion of two powers—one for God and another one for David representing the Messiah.

Rabbi Akiva’s perspective demonstrates that such interpretations were not foreign to early Jewish thought. In fact, were the mainstream view.

Rabbi Akiva believed that God and the Messiah could hold distinct but interconnected roles in heaven. His reading of Daniel suggests that the “Son of Man” embodies a divine role, resonating with Christian beliefs regarding Jesus’s nature as both divine and human.

Rabbi Akiva believed that God and the Messiah could hold distinct but interconnected roles in heaven. His reading of Daniel suggests that the “Son of Man” embodies a divine role, resonating with Christian beliefs regarding Jesus’s nature as both divine and human.

Boyarin continues on page 140.

However, not all rabbis agreed. Rabbi Yossi the Galilean rebuked Akiva, saying, “Akiva, until when will you make the Shekinah profane?” He proposed that the thrones represented judgment and mercy.

However, not all rabbis agreed. Rabbi Yossi the Galilean rebuked Akiva, saying, “Akiva, until when will you make the Shekinah profane?” He proposed that the thrones represented judgment and mercy.

But it’s clear, Rabbi Akiva is taking the clearer and simpler interpretation of the text. And when you understand Jewish tradition, they say that the clear and simple interpretation of the text is the preferred understanding of the text.

This leads us to ponder however, why modern Jewish leaders, especially Rabbi Singer, may downplay this interpretation. Given the historical context, would it not be more accurate to acknowledge the nuanced perspectives that existed among early Jewish scholars?

The Baraita and the God-Man Theology

The Baraita collects oral traditions that the Talmud does not include. These teachings illuminate diverse Jewish beliefs before the Talmud was complete. I obviously reject the oral law, but Rabbi Tovia Singer accepts it.

The Talmud is the oral law Rabbinic Judaism teaches that God gave to Moses alongside the Bible.

In the case of Rabbi Akiva, the Baraita preserves his “controversial” interpretations of Daniel 7. This underscores how early Jewish thought was far closer to Christianity that people like Singer would have you believe.

Also, the “God-Man theology” refers to the belief that the Messiah is both divine and human—a central tenet of Christian theology.

This concept posits that Jesus, the “Son of Man” mentioned in Daniel 7 and elsewhere, is not only a human figure but also God incarnate.

Biblical Basis: Daniel 7:13-14 explains that the “Son of Man” approaches the “Ancient of Days” and is given eternal dominion, glory, and a kingdom. The Son of Man in this passage is both divine and human. This is because He receives worship, has an eternal reign, and rides the clouds. These are things due only to God.

Jewish Context: Dr. Daniel Boyarin and others have suggested that elements of this theology were not alien to early Jewish thought but in fact, were the mainstream view. For instance, Rabbi Akiva’s interpretation of Daniel 7 includes the idea of the Messiah as the “Son of Man” who shares divine authority and rulership.

Boyarin highlights this as evidence that early Jewish beliefs could accommodate the concept of a God-Man, though this was later rejected by mainstream Judaism.

But I want you to understand that Rabbi Akiva comes 100 years after Jesus. This means, this was the mainstream view, even after the New Testament had been written.

The Angel of the Lord: Authority and Divine Presence

The Angel of the Lord: Authority and Divine Presence

Rabbi Singer vehemently opposes the notion that early Jews could have worshipped anything akin to two divine powers.

He argues that the “Angel of the Lord” in the Hebrew Bible is simply a messenger without divine status. However, a deeper exploration of the texts may reveal layers of meaning that challenge this viewpoint.

In Exodus 23:20-21, we read about the Angel sent by God, tasked with guiding the Israelites. This figure has a significant role, not merely as a messenger, but as a divine representative.

“Behold, I am sending an Angel before you to guard you on the way and to bring you to the place that I have prepared.” — Exodus 23:20

The next verse urges the people to listen to the Angel’s advice. It warns that rebellion against Him could bring serious consequences.

“Pay attention to him and listen to what he says. Do not rebel against him; he will not forgive your rebellion, since my Name is in him.” – Exodus 23:21

Rabbi Singer claims that this angel lacks independent agency and cannot forgive sins. But the passage doesn’t say He cannot forgive sins, but He will not forgive sins. There’s a big difference there.

Scripture includes instances where people show deep reverence toward the Angel of the Lord. These moments highlight a complex interaction between the divine and earthly realms.

“And the Commander of the Lord’s army said to Joshua, ‘Take off your sandals from your feet, for the place where you are standing is holy.’” – Joshua 5:15

This moment is emblematic of worship; Joshua, recognizing the divine nature of the encounter, removes his sandals—an act of submission and honor. Just like Moses did at the burning bush.

Also in Zechariah chapter 3, the Angel of the Lord forgives sins there as well.

Worship and Divine Authority

Rabbi Singer argues that no one would worship created beings like Michael or Gabriel. And that is true. But Christians are not claiming the Angel of the Lord is an angel like Michael or Gabriel.

Rabbi Tovia Singer takes a wooden interpretation of the word “angel” in Hebrew (Malakh). That word simply means a “messenger”; it doesn’t tell us the nature of the messenger, it just tells us that they are bringing a message.

For example in Genesis 32 (verse 4, 7), human beings are called “Malakh” (messengers). They were not “angels”. The word Malakh tells us what the person is doing. It is not trying to tell you the nature of the person as Singer would have you believe.

The context determines that.

The worship of the Angel of the Lord suggests that this figure possesses an authority separate from other angels. Unlike Michael and Gabriel, whom Singer suggests are not objects of worship, the Angel of the Lord is depicted as holding a significant divine status.

Moses’ encounter with the burning bush demonstrates the divine presence embodied in the Angel. Likewise, Genesis 19 presents a striking account of God’s judgment on Sodom and Gomorrah.

Rabbi Singer argues that angels are called the divine name in Genesis 19. Throughout Genesis 18 and Genesis 19, one of the three is consistently called Hashem. Speaking to the three men, Lot says Hashem.

Singer says this is proof angels are called HasShem.

Now everything before this, and everything after this, all points to one individual being called Hashem. Because of this, it’s better to say and to interpret this passage as Lot saying it to them by speaking to the Lord, and not Lot calling all three men Hashem.

In Genesis 19:21-22, God responds directly to Lot’s request, not all three:

“And he said unto him, See, I have accepted thee concerning this thing also, that I will not overthrow this city, for the which thou hast spoken. Haste thee, escape thither; for I cannot do anything till thou be come thither. Therefore, the name of the city was called Zoar.”

This response highlights God’s personal involvement. God agrees to spare the city of Zoar. The angels do not make this decision—this is God’s direct intervention. His words reinforce that He, not the angels, has the ultimate authority over the judgment of Sodom.

Then, in Genesis 19:24-25, we read:

“Then the Lord rained upon Sodom and upon Gomorrah brimstone and fire from the Lord out of heaven; and he overthrew those cities, and all the plain, and all the inhabitants of the cities, and that which grew upon the ground.”

This verse is crucial. It explicitly states that the judgment came directly from “the Lord out of heaven.” There is no indication here that the angels executed this action.

The text portrays God as the singular divine actor who carries out this judgment, underscoring His sovereignty and authority.

Throughout Genesis 19, the text identifies one of the three men who visited Abraham as God and describes the other two as angels.

This distinction matters because Lot addresses the group as “my lords” in Genesis 19:18. This is why it’s clear his plea is specifically to God.

The angels, though divine agents, are not recipients of divine worship or authority in this passage.

This distinction helps clarify the nature of God’s presence: He often uses angels as His messengers, but they do not share in His divine identity.

Attempts to conflate the angels with God ignore the careful wording of the text through the chapters.

Misunderstanding Prophet Isaiah

Misunderstanding Prophet Isaiah

We see another example of misunderstanding from Rabbi Singer, regarding the divine name in Isaiah 7. He claims that the text calls Isaiah by the divine name or equates him with God, but the text does not support this interpretation.

In Isaiah 7:3, we read:

“Then said the Lord unto Isaiah, Go forth now to meet Ahaz, thou, and Shear-jashub thy son, at the end of the conduit of the upper pool in the highway of the fuller’s field.”

Here, the Lord directs Isaiah to deliver a message to King Ahaz. The divine name is used to show that the message comes directly from God, not from Isaiah’s authority.

This pattern continues in Isaiah 7:10:

“Moreover the Lord spake again unto Ahaz, saying…”

The repetition of “the Lord spake” makes it clear that Isaiah is not being called by the divine name. Instead, the text emphasizes that God is speaking, just as He did earlier in the chapter.

Final Thoughts

The exploration of “Two Powers in Heaven” discussion reveals that this concept is not merely a Christian innovation, but has deep roots in Jewish tradition and Scripture.

From Rabbi Akiva’s interpretation of Daniel 7, to the angelic figures, these perspectives challenge oversimplified narratives. While Rabbi Singer offers his rebuttal, his approach raises questions about transparency and interpretation of the texts.

This dialogue reminds us of the importance of examining the Scripture with an open mind. If you’re interested in seeing another example of this, check out this article about a “Christian Preacher” who became a Muslim.

WATCH THE VIDEO

Recent Comments