Is the Trinity Biblical or a Bad Belief?

Is the Trinity biblical or a bad belief that developed over time? Today, we’re exploring this question by looking at both history and scripture. Did the disciples believe in the Trinity, or was it introduced hundreds of years after Jesus?

This topic holds great importance since, for those of us who believe in the Trinity, misunderstandings about it can lead to accusations of idolatry or blasphemy. If we’re wrong, the stakes are indeed high.

The Historical Perspective on the Trinity

In a recent video, I discussed the Trinity using only Old Testament passages. I mentioned doing a New Testament study if people were interested, and while this isn’t that post, let me know if that’s something you’d like to see.

Today, I’ll approach the Trinity from a historical angle, referencing scripture as always.

One of the main sources I’ll refer to is a book [1]Borderlines by Dr. Daniel Boyarin, by a Jewish scholar, whose work has shed light on the Trinity’s historical background.

His research supports the idea that the Trinity wasn’t a later Christian invention or a concept influenced by Greek philosophy but was present among Jewish beliefs during and even before Christ’s time.

Perspective on John’s Gospel and the Logos

Dr. Boyarin shares a pivotal idea about the Logos, or the “Word,” that aligns with the Gospel of John. In John 1:1–2, we read,

“In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God.”

This passage powerfully affirms Jesus’ divinity, showing Him as distinct yet unified with God. While many scholars claim Greek thought influenced John, Dr. Boyarin disputes this, asserting that John’s Gospel is deeply rooted in a Jewish worldview.

During one lecture, Dr. Boyarin encountered a student who felt he was “taking away” the Gospel from Christians with his interpretation.

But Boyarin’s point was to emphasize the Jewish foundation of the Gospel of John, showing how Christianity and Judaism may be closer than we think.

The Influence of Jewish Beliefs on Christian Theology

The Influence of Jewish Beliefs on Christian Theology

In the book, Dr. Boyarin recounts being asked by Christian ministers why he wasn’t a Messianic Jew, especially given his interpretation of Jesus as the Logos—a concept they closely associate with Christian theology.

His response highlights a crucial point: beliefs in the Father and Son were not uniquely Christian in the first century. They were common among Jewish communities as well.

Dr. Boyarin also shares that his work received pushback from Jewish scholars who warned him about the impact of his findings.

A respected colleague expressed concern that Boyarin’s research could support Christian theology, to which Boyarin responded by sharing his findings, even at personal and professional risk.

A respected colleague expressed concern that Boyarin’s research could support Christian theology, to which Boyarin responded by sharing his findings, even at personal and professional risk.

The Doctrine of the Logos and its Jewish Roots

Dr. Boyarin explains that Jews widely accepted the doctrine of the Logos, a divine intermediary between God and humanity, both before and after Christianity emerged.

Early Jewish thought regarded God’s Logos or Wisdom as a distinct person, paralleling New Testament descriptions of Christ as the mediator between God and humanity, as in 1 Timothy 2:5.

Boyarin’s work supports the argument that the Logos theology present in the New Testament was “native to Judaism.” He suggests that John 1:1-18, often viewed as a “Hellenized” text, was, in fact, a Jewish concept consistent with other Jewish writings of that time.

This alignment implies that the New Testament theology wasn’t an addition to Judaism but a fulfillment of Jewish thought.

Rabbi Akiva and the Belief in a Divine Messiah

Rabbi Akiva and the Belief in a Divine Messiah

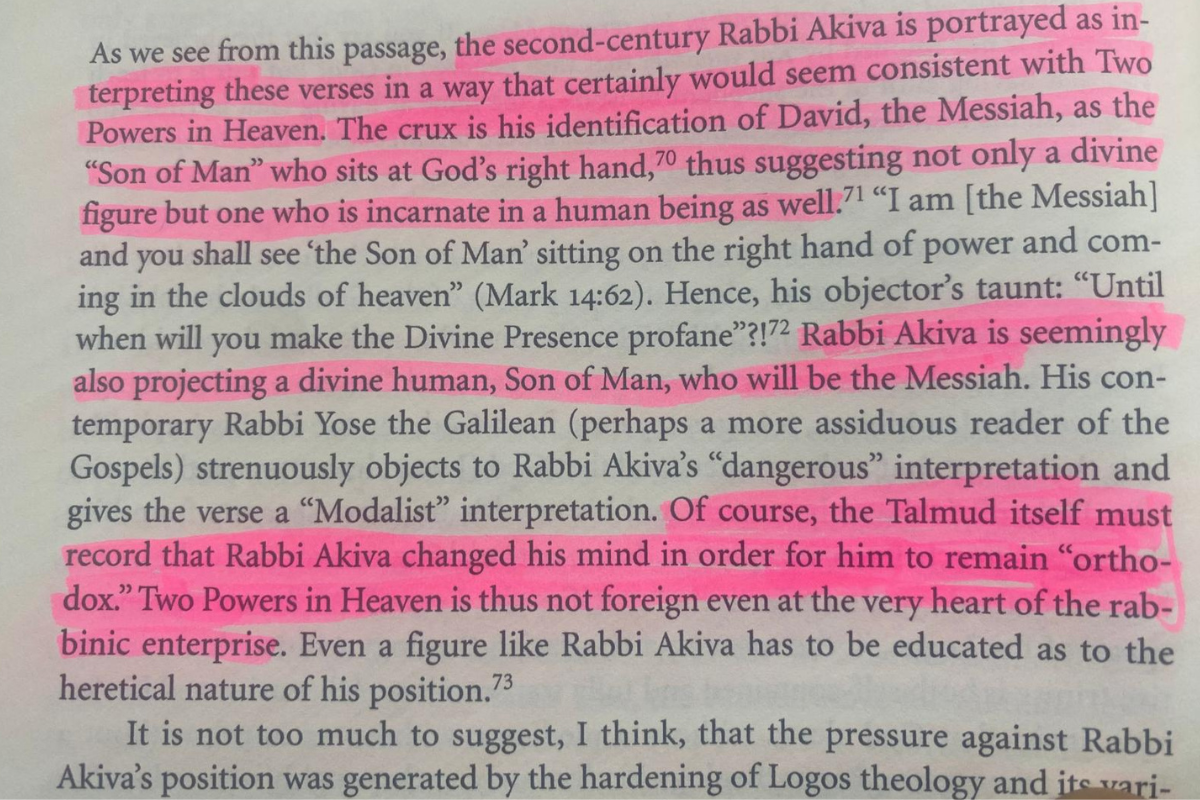

In another key point, Dr. Boyarin cites Rabbi Akiva, a significant figure in Jewish history, who interpreted Daniel 7’s “Son of Man” passage as referring to the Messiah.

At Jesus’ trial, he references this prophecy, describing himself as the “Son of Man” who will “come with the clouds of heaven” (Mark 14, Matthew 26).

Akiva embraced the passage as a vision of the Messiah approaching the Ancient of Days to receive worship, although Rabbi Yose later opposed this view due to its Christian implications.

Akiva embraced the passage as a vision of the Messiah approaching the Ancient of Days to receive worship, although Rabbi Yose later opposed this view due to its Christian implications.

Boyarin argues that Akiva’s acceptance of this passage aligns with early Jewish beliefs in a divine Messiah, similar to the Christian doctrine of the God-Man.

The view held by Akiva and others reflects that the early Jewish understanding of the Messiah included divinity, a perspective lost in later Rabbinic Judaism.

Two Powers in Heaven: A Common Belief in Early Judaism

Boyarin also references Dr. Alan Segal’s work, “Two Powers in Heaven,” which explores a similar idea: that many Jews in the first century held a Binitarian view of God, with God’s Word as a distinct yet divine person.

This perspective was prominent until the destruction of the Second Temple, after which Rabbinic Judaism developed a more rigid monotheism.

Boyarin’s research reveals that many Jews believed in a “second power” in heaven, a divine figure that would later become identified with Jesus in Christian theology.

This view was neither foreign to Judaism nor invented by Christians, as it existed in various Jewish circles long before.

Trinity: A Long-Standing Belief Rooted in Scripture

Dr. Boyarin’s work shows that the early church was mostly Jewish, with believers viewing Christ as fulfilling God’s Wisdom and Power from the Old Testament. Many Jews in the first century widely held Trinitarian-like beliefs, or at least a precursor to the Trinity.

The “new” Christian doctrine actually grew from an established Jewish belief in God’s multiple expressions: the Father, Son, and Spirit.

Reflecting on this unity in belief can inspire us to strengthen our approach to sharing our faith. If you’d like to explore ways we may fall short or succeed in evangelizing, check out our post on how we can share the Gospel to others.

May these insights encourage us to continue sharing the profound truths of our faith with clarity and conviction.

WATCH THE VIDEO

References

| ↑1 | Borderlines by Dr. Daniel Boyarin |

|---|

Recent Comments